Every Monday night at 6:30 p.m., seven-year-old Matthew comes for a piano lesson. Some days, these lessons are 80% discipline and 20% playing but this week’s lesson was an exceptional contrast.

In preparation for our lecture recital, Steve and I had moved the piano from it’s usual front right position to front and center (and rotated 180-degrees). This change to our normal lesson scene made an immediate difference with Matthew. The curly-headed, wiggly child sat right down and flipped his book open to our newest page. “Are we starting with this piece?” I asked, pointing to the first of the two. Without a word, he brought his hands up to the keyboard and began to play. He meant business! I sat to the side and observed until the end of the piece. Matthew has an excellent sense of rhythm so generally it’s just fingering and tonal patterns that we need to review. This performance, however, required no review! He played the song in it’s entirety while chanting the text. I was impressed!

We moved on to the second piece on the page by reviewing the rhythm/text. After tapping and chanting, I asked him to find his hand position. Again, he played straight through, while chanting the text with no issues!

Normally, by this point in the lesson, I would be kindly asking him to take his feet off the pedals, sit still, play with only fingers 2 and 3, etc. Since he was so focused and playing so well, I encouraged him to explore the change in sound when adding a little pedal. He played very gently – adding about half of the sustain pedal throughout.

At the end, I asked, “How did that change the sound?” He had an immediate response. “It stays,” he said simply. “Yes!” I replied enthusiastically. “It makes the sound last longer, doesn’t it?” “Yes, and if I were just playing notes like this-” he stopped to demonstrate a pattern of steps “then I wouldn’t need the pedal. But if I were playing here [high register] and then I wanted to go down here [moving to the mid-low register] then I would need the pedal.” What an insightful response! It became clear to me that Matthew not only recognized the sound difference but knew how he would use it in the future as a way of connecting patterns in different registers!

Having recently learned about 2nds, playing on white keys (this book starts on the black keys), and dotted half notes, I asked Matthew to improvise a piece that incorporated all three things. He thought for a minute before beginning. Thoughtfully, he played a stepwise melody with a repeated rhythmic motive. He used both hands and a wide range of keys. The piece ended rather abruptly but from the look on his face, this was intentional.

“That was beautiful, Matthew!” I said. “What’s the name of that piece?” “I haven’t decided yet,” he said in a matter-of-fact way. “Let’s ask your grandma what she thought,” I suggested. “I thought it sounded whimsical,” she said. Seeing the perplexed look on Matthew’s face (“What the heck does that mean?!”) she quickly added, “Like playing with toys.” “Hmm, what do you think, Matthew?” I asked. “Toy Days,” he stated. And “Toy Days” it was.

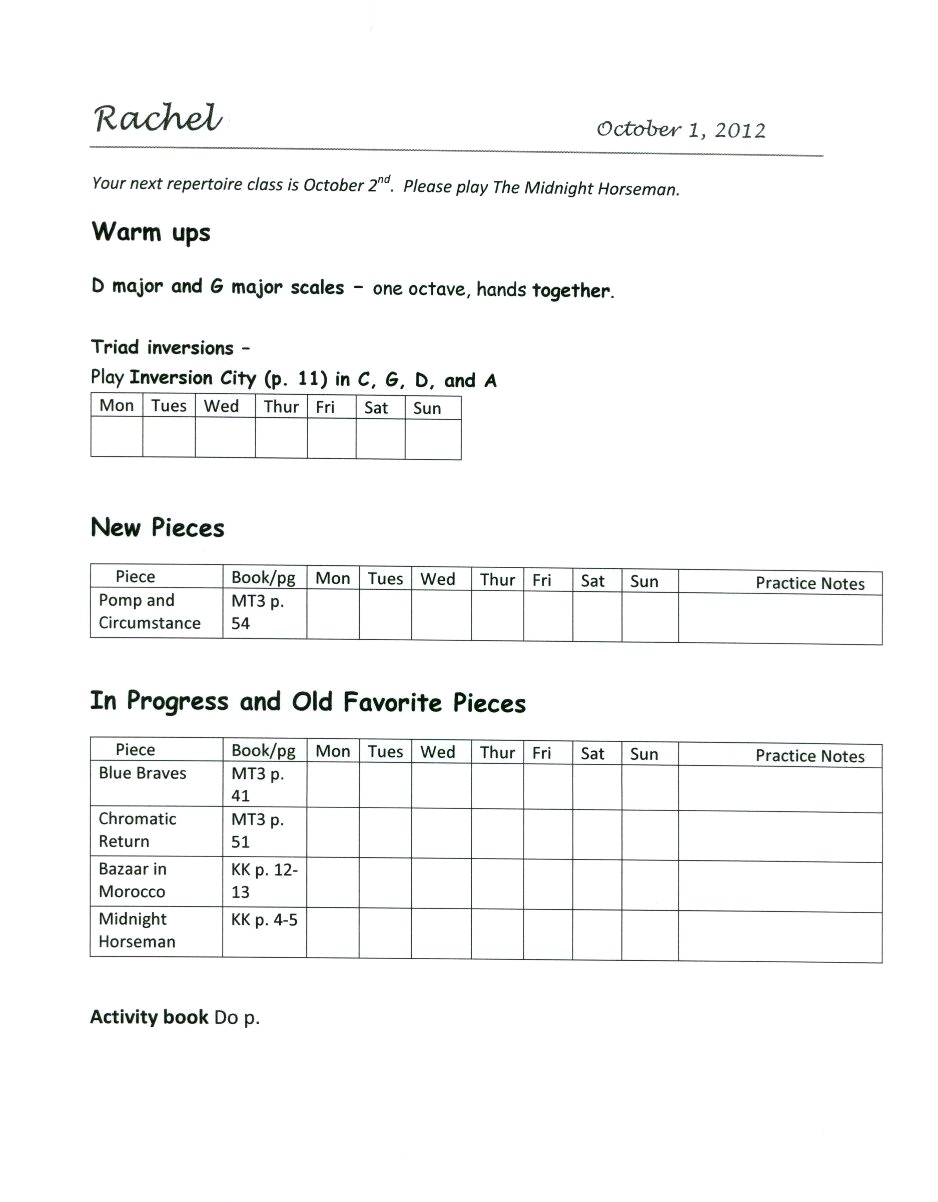

We moved back in the book to review his recital pieces – “Inchworm” and “Playing Frisbee.” We work on text from the very beginning of learning a new piece but in preparation for the recital, I’ve been working on having Matthew think the words internally instead of speaking them out loud. We reviewed this for both pieces and as I joined him on the bench to add the duet part, I reminded him about bringing our hands up to the keyboard at the same time and lifting our hands off the keys and back to our laps at the end of the piece. His grandmother was very impressed.

I had one more piece to review – “Merrily We Roll Along.” This is a great example of knowing/singing a song one way and reading it another. This elementary piano book carefully presents this song within a 3-note range for each hand and with only basic rhythms (for instance, no dotted rhythms). I believe that reading is important, but I also know that Matthew knows this song with a different rhythm. I’m not going to correct him with the simplified version when he can hear and play the more complicated version. All I had to do was turn to the page and he began to play.

I had turned for just a minute to make a comment to his grandmother about practicing but I could hear him working out this song by ear. He was looking at the book but we both knew he wasn’t really reading it. He was singing to himself and when he played a wrong note, he would say to himself, “Wait!” and then begin the phrase again and again until he figured it out. He didn’t stop until he could play all the way to the end. I thought this was excellent and praised him for using his ear to self-correct. I played my accompaniment for him and we sang the melody together (with the familiar dotted rhythm). After that, it was much easier to play both parts because he already had an idea of how the two parts fit together.

We ended our lesson time with a few preparation steps for a new song – reading the text in rhythm and tapping while chanting. We discussed the implications of the title (“Parade”). “Have you ever marched in a parade?” I asked. “No, but I’ve seen a parade before,” he answered. “Well, what do you think would happen if you were marching in a parade and suddenly, you decided to stop?” “You would get run over!” he replied with big eyes. “Probably so!” I said. “That’s what this song means when it says, ‘Keep the step!’”

Lessons like these remind me why I love teaching. The creativity, the innocence, the playfulness, and the imagination make music so much more fun! Can we all be a little more like seven-year-olds sometimes?