*Disclosure: I get commissions for purchases made through links in this post.

Last year, I spent some time observing at the New School for Music Study in Kingston, NJ (read my notes here, here, and here).

This school, founded in 1960 by Frances Clark and Louise Goss functions as a keyboard pedagogy lab: pedagogy students gain teaching experience, community members gain instruction, and new teaching approaches are constantly being tested and evaluated.

One of Clark’s strong beliefs was that students should be taught to be self-motivated learners — this essentially makes the teacher dispensable!

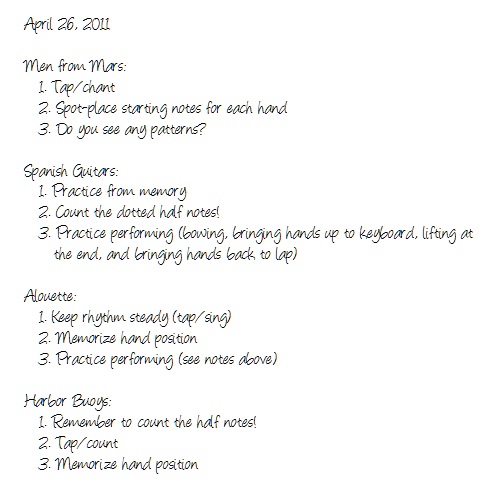

In trying to develop independent learning in my students, I recently began introducing “practice plans” with my students during lesson time (an idea I observed at the New School). Practice plans are 2-4 specific items or practice strategies per piece, neatly written on a sheet of paper that they can keep out next to their books to (hopefully) better organize their practice time at home.

Think of how much learning takes place at home during the week! If a student practices 20 minutes a day, five times a week, that’s 100 minutes of solitary time spent on these pieces (as compared to the measly 30 minutes they spend with me each week).

Here is an example of what this sheet looks like:

This student (age eight) is working out of The Music Tree, Part 1. At the beginning of today’s lesson, we reviewed the last practice plan and checked off the completed items (she was very honest about what she had and had not completed!).

After reviewing the pieces in progress and performing her two recital selections, we wrote out a new practice plan together. This is not a practice notebook where I sit and scribble notes while she plays and I hope she goes home and reads them later. Practice plans are collaborative.

*As a side note, I do keep a lesson notebook for my own purposes — mainly, keeping up with student progress and repertoire assignments.

“What are two ways you can practice this new piece?” I asked today.

Erin made a suggestion, I made a suggestion, and I made sure she could demonstrate whatever it was we were writing down. After all, writing “tap/count” is great, but if she doesn’t know what it means when she gets home, it’s not a real practice item.

The exercise of talking through a practice plan for each piece doubles as an assessment tool for me: by having students make suggestions for their practice time (setting their own goals), I have a better understanding of what they’ve learned and how they are applying and reusing ideas and strategies from previous pieces we’ve studied. Also, I find students are more accountable to me the next week when they have to report on the effectiveness of their practicing — they take more responsibility for their progress.

For more information on Frances Clark, visit the Frances Clark Center for Keyboard Pedagogy website.

I’ve often been advised to “make the most of opportunities” – I’m sure you’ve been there, too. Sometimes an opportunity presents itself out of nowhere – maybe it’s an extra time commitment, maybe it’s out of your comfort zone and just when you’ve convinced yourself to pass it by, suddenly the opposing voice in your head says, “Wouldn’t this be a great experience?” In my case, the opposing voice usually wins.

I’ve often been advised to “make the most of opportunities” – I’m sure you’ve been there, too. Sometimes an opportunity presents itself out of nowhere – maybe it’s an extra time commitment, maybe it’s out of your comfort zone and just when you’ve convinced yourself to pass it by, suddenly the opposing voice in your head says, “Wouldn’t this be a great experience?” In my case, the opposing voice usually wins.